When I read Tattoos on the Heart, I went into full-body sobbing. My face got wet and body went into spasms. This has never happened to me before while reading a book. What gives?

I think the reason for my sobbing is that I was bullied as a kid. The wounded part of me resonated with the stories in this book. The gang members — “homies” — Father Greg works with were abused and excluded growing up, just like me.

Father Greg lets them back into the house of belonging through the door of unconditional love. Love is what the homies need. Love is what I needed, and still need. Love is what we all need.

Love — no matter what.

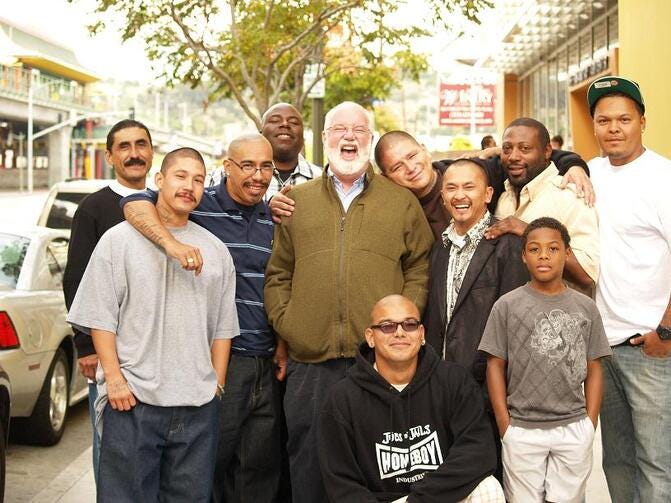

Tattoos on the Heart is about Father Greg’s work with Homeboy Industries, helping gang members in LA with job training, tattoo removal, and emotional support. But it’s really about love.

A while ago, I answered a bunch of questions as part of a yearly reflection exercise. One of these was: “Did I love well?”

That question was like a punch in the throat.

I didn’t know if I loved well. I didn’t even really know — if I’m being honest — what love was.

Tattoos on the Heart doesn’t define love in words. It shows the reader what love is through the example of Father Greg.

Is a good life about adventure, enjoyment or personal gain? Is it about achieving good outcomes for the world? Or is it about love?

“Nothing depends on how things turn out, only on how you see them when they happen,” says Father Greg.

Father Greg is not obsessed with statistics and numbers. You can be doing great on paper, but if your heart isn’t loving, your life will be empty.

“The beginning of wisdom is calling things by their right name,” Father Greg says. “When we see clearly, we behave impeccably.”

Father Greg clearly sees the loads that people have to carry. “In 30 years of working with gang members, I’ve never met a bad guy. Every homie I know that has killed someone, has carried a load 100x greater [than I’ve had to carry]. Most of us have never born that weight…Have awe at what people have to carry, not judgement at how they carry it,” says Father Greg.

Tattoos on the Heart is filled with horrific tales of trauma. A father who beats his son with a pipe. A mother who holds her son’s head in the toilet and tries to drown him. In the midst of such horror, is it any wonder that people recreate patterns of violence?

Father Greg talks about “attachment repair.” In Barking to the Choir, the sequel to Tattoos, there’s a story about a boy who is amazed that a social worker brought him a box of Triscuits. It blew the boy’s mind that he had mentioned that he liked Triscuits, and she later got him a box. This meant that she was thinking of him when he wasn’t there, something he never experienced in any other relationship in his life. That social worker is filling the boy’s cup with love.

“In the course of their good journey, they reclaim a childhood they’ve been denied,” says Father Greg. This is a childhood where they were seen for who they were, in all their humanness.

Father Greg becomes the father that so many homeboys and homegirls lacked. He accepts them, listens to them, unconditionally.

The unconditional in unconditional love means not expecting anything in return. It doesn’t mean there aren’t boundaries. Father Greg enforces boundaries with gang members. He fires them from Homeboy Industries if they don’t show up to work. But that doesn’t mean he stops loving them.

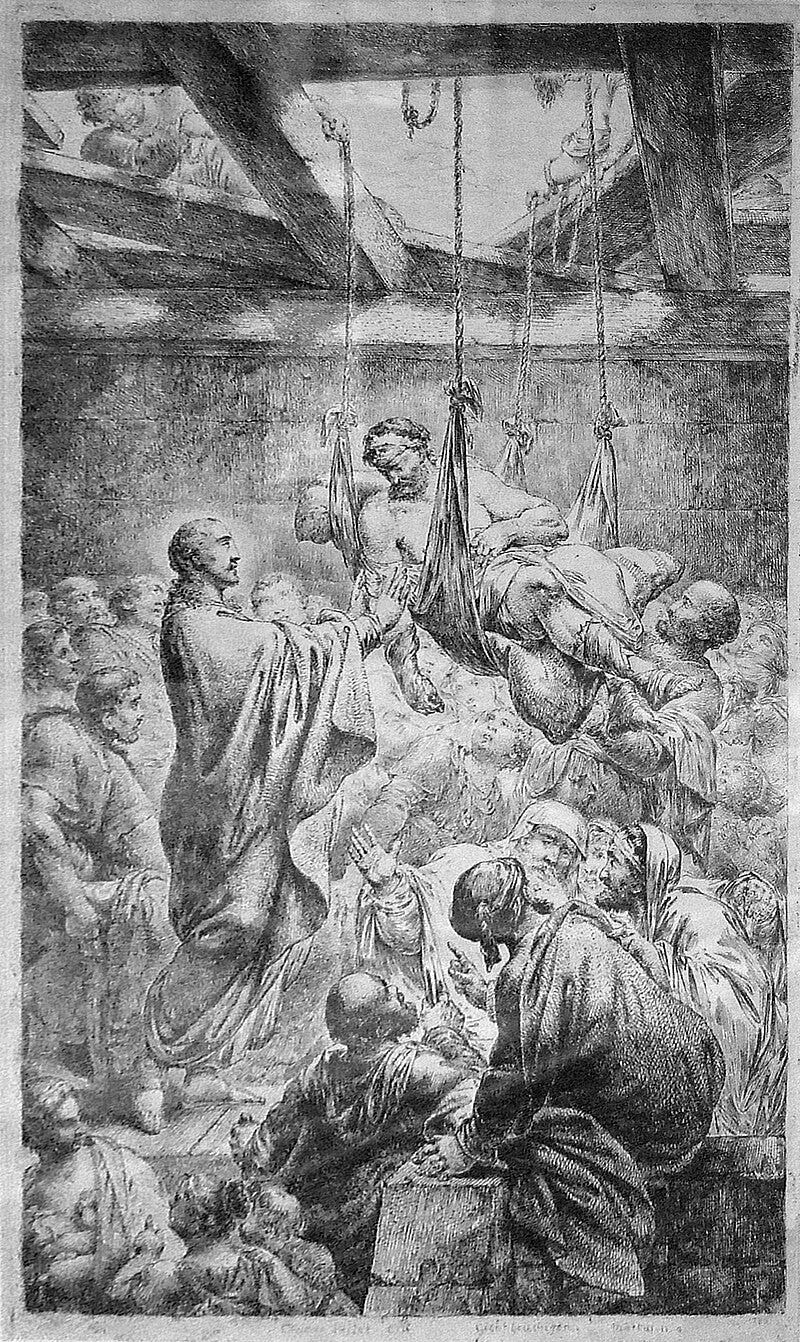

Father Greg tells the parable of a bunch of men in a house with Jesus. The house is so full that the last man — a paralyzed man — has to come in through the roof. The point of the story is that Jesus lets everyone into the house of belonging. Ditto for Father Greg.

Greg talks a lot about kinship. He recounts a story of a former gang member on a plane, telling a flight attendant about Homeboy Industries, who starts sobbing. “She saw your inner goodness. Kinship, at 20,000 feet.”

Kinship is the sense that we are all part of one human family. “A measure of our kinship is the certainty that no life holds more value than another,” says Father Greg. His work is largely a reaction to the pernicious idea in our culture that some lives are more valuable.

Society has come a long way in many areas (racism, sexism…), but devaluing people is still very much in style. Whether the them are of a different political stripe, or a different nationality, or just “that asshole” who did that thing, judgement — the tendency to devalue — seems to be hard-wired in our souls.

While I don’t subscribe to Catholic theology, I find the idea of original sin — the notion that we have inborn destructive tendencies that we have to work against — deeply useful. Minimizing our judgements can open our hearts to love.

In the documentary G Dawg, Father Greg asks the question, “What are fates worse than death?” One of these, I think, is being stuck in judgement.

Father Greg not only uses empathy to fight judgement, he also uses humor. He tells the story of Crazy Shopping Cart Lady Lucy who asks him for money. Father Greg gives her $20 bucks. “If you weren’t a priest, I would rock your world,” Lucy says.

“Lucy, best offer all day,” says Greg.

Humor, in the hands of Father Greg, is another tool for acceptance and love.

Humility is another. Humility, Greg says, is not a downsizing, but a right-sizing. “There is something exhilarating about finding our right size in our nothingness.”

I did a hike on the Na’Pali coast of Kauai yesterday, and gazed at the expanse of the ocean, stretching from one side of my vision to the other. I found my right size.

Marcus Aurelius said: “Forget everything else. Keep hold of this alone and remember it: Each of us lives only now, this brief instant. The rest has been lived already, or is impossible to see. The span we live is small—small as the corner of the earth in which we live it. Small as even the greatest renown, passed from mouth to mouth by short-lived stick figures…”

We are short-lived stick figures.

Praise and blame, Father Greg says, are equally seductive. He talks about “moving to the center.” By this, I think he means moving to the objective reality: we are small. All we can do is to live our lives in pursuit of virtue. Inherently, we want to pursue virtue, and even if we mess up, we still have an inner goodness, a hard-wired desire to seek it.

Father Greg tells the story of Larry David, loved by millions, who got bent out of shape about one person who screamed “you suck” at him at Yankee Stadium. “The whole world can love us, but one person can raise an eyebrow and you feel excluded,” says Father Greg. He goes on to talk about a woman who told him after one of his talks: “I hate you and everything that Homeboy represents.” Her son had been killed by a gang member.

Father Greg viewed her as a woman imprisoned by hatred. He knew that her hatred was hers. It was about her pain, not about his actions, and he didn’t take responsibility for it. He found his center.

I’m not done learning from Father Greg, and there may very well be more posts here about him.

If I had to sum up what I’ve learned from him so far, it’s this:

Love = truly listening = accepting someone for exactly who they are right now, without expecting anything in return.