This post contains what I learned about life from from the biographical documentary Dealt, and also from this podcast about Turner. Both were fantastic. Spoilers below.

Dealt catalyzed me to think about my life. Here are five life-lessons I came to, after much thought:

1. To have a good life, being exceptional is not necessary or sufficient.

Magic was one of my first true interests as a kid. I still remember the magician who came to our summer camp and did a series of amazing tricks: putting cards inside balloons, pouring infinite water out of a vase, teleporting an audience member’s dollar bill inside a lemon.

I was stunned, and instantly became obsessed with magic. I went to magic shops. I bought magic books. I performed magic in the Variety show at my middle school. But after a few years, my interest in magic faded. I didn’t have the level of motivation to practice tricks obsessively. I got into other things: writing, academics. I didn’t have what it took, at that point in my life, to devote countless hours to magic.

Later in my life, I got interested in going into two other fields: science, and movie-making. These three fields — Magic, science, and film-making have in one thing in common: a low carrying capacity.

In ecology, the carrying capacity of an ecosystem is how many organisms of a certain species it can support. In a similar way, society can support a great number of some professionals (e.g. doctors) and much fewer of others (e.g. magicians). This means that to be a paid magician, you have to be quite exceptional. To be a paid doctor, it’s OK to be middle-of-the-pack.

In his book How to Live, Derek Sivers outlines dozens of approaches to life that are valid AND contradictory. One chapter says to pursue mastery, what he calls mono-mania. Another chapter says balance is the key.

All of these approaches to life can work for people, just they work better for some people than for others. Humanity is an ecosystem, and to make this world work, it takes all different kinds.

One feeling I had when I watched Dealt was a sense of grief: I have not become a successful magician. But the more I reflected on this, the more I realized that I have a lot of awesome things about my current profession as a neurologist. I get to occasionally help people in very significant, even-magical, ways in their real lives. Just yesterday, I looked at two brain scans, before and after a treatment, and the scan after the treatment was markedly improved.

In addition to the magic of doctoring, I get to use different facets of myself. At certain moments with my patients, I can play the role of a teacher, a psychotherapist, and even, a clown.

The documentary helped me accept that I’m a generalist. Yes, I will probably never get to the level of mastery that Turner has with cards, or honestly, with anything else. He is truly exceptional. Top 5 in the world.

Turner has put in a level of work and commitment that few people are willing to invest. A level of commitment that I was not willing to put in.

We are always missing out. Just as I’m missing out on being a professional card magician and karate black belt, Turner is missing out on being a neurologist.

Researching Turner lead me to this article, written by a Michael Friedland, a card magician who also looked up to Turner. Friedland ended up not pursuing magic as a career. The risks of not “making it” and the level of mono-maniacial focus required, were not worth it for him.

During the summer of my freshman year of college, I worked in LA as an intern at a screenwriting agency. I met a lot of people who were just as talented as me, but they were not doing work that I would have wanted to do. I looked at myself in the mirror, and realized that I probably did not have what it took, in both talent and motivation, to end up in a Hollywood career that would be meaningful for me (as an auteur director, like the Coen brothers or Quentin Tarantino). So I chose to pursue medicine — a field with a higher carrying capacity that does not require such exceptionalism.

In the end, I’ve realized that exceptionalism, while impressive, is not necessary or sufficient for a good life.

Mark Manson puts it very well:

Some of the most important things in life are not extraordinary at all. Things like raising a kid well. Things like taking care of your health. Being an honest and good person to your friends and family. These are not extraordinary things. In fact, they are the most ordinary things. And I think they’re ordinary things for a reason: because they’re the most important.

2. Minimization of secrets — from oneself and others — is a good thing to strive for.

On it’s surface Dealt is about cards and magic, but on a deeper level it’s about our relationship with our weaknesses.

In the first few minutes of Dealt, we learn that Richard Turner is blind. You might think that blindness is Turner’s problem.

Turner doesn’t want sympathy points for being blind. He wants his accomplishments to speak for himself and they do: audiences who watch him never learn that Turner is blind. He’s perfected how to appear as if he can see.

This denial seems to be working for Turner, but he has to lean heavily on his son and wife to function in daily life. His son Asa Spades Turner (no joke: this is his son’s real name) functions as his manager. Turner uses his wife Kim as his seeing eye dog. After a while, Kim and Asa resent the role that Richard puts them in.

Turner’s denial of his blindness is a paradox. In one sense, it’s a major contributer to his greatness. Because he didn’t want to be defined or limited by his disability, Turner worked his ass off and became truly great, at both magic and karate.

On the other hand, the fuel driving his achievement is, at least in part, based in anger and shame.

Turner was bullied as a kid. He talks about how he was called “Mr. Magoo” by kids growing up. They’d ask him how many fingers they were holding up, and he’d say “two.” They were holding up middle fingers.

“I hate to admit it, but I broke down and cried,” Turner says.

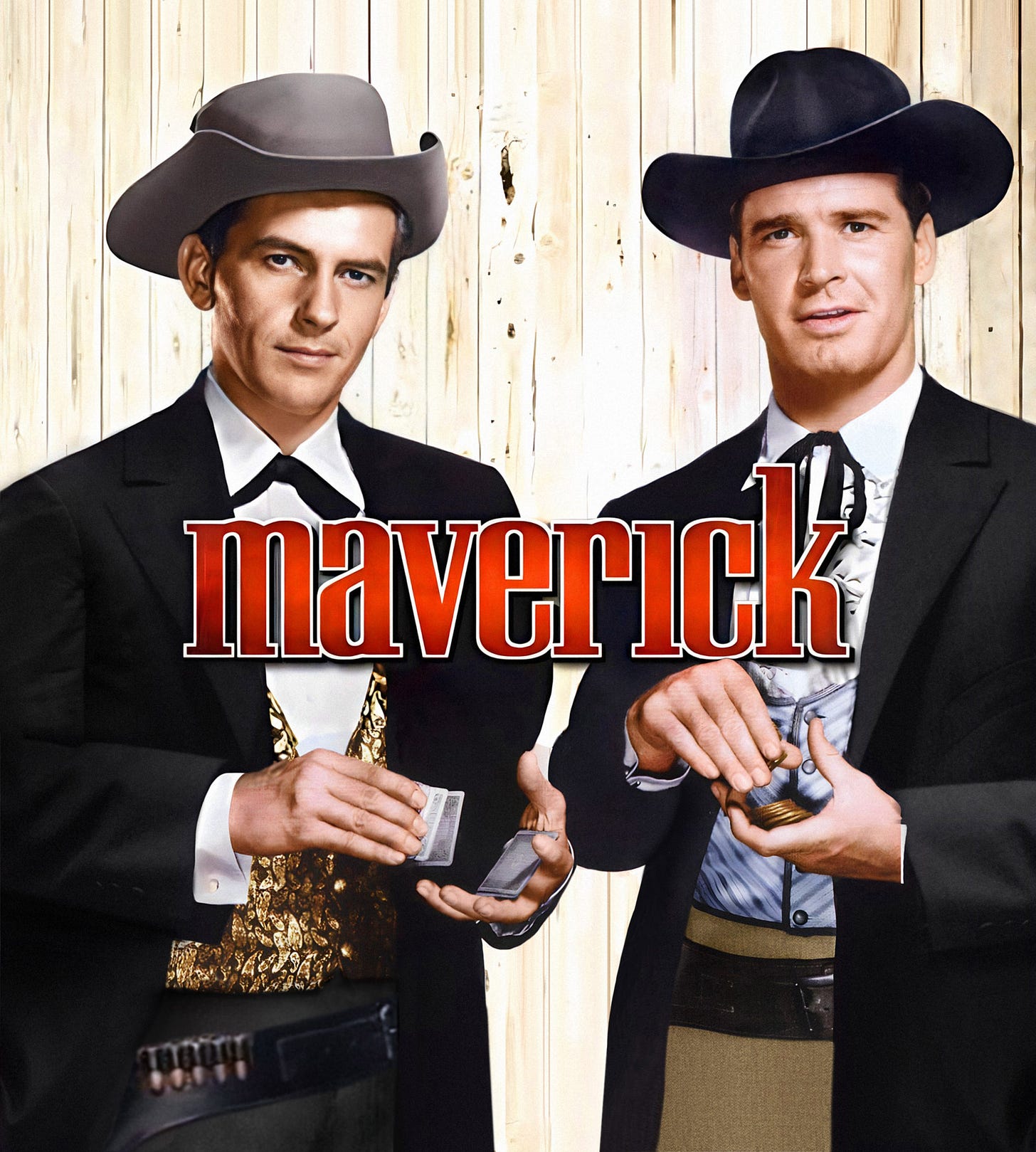

Turner became a card magician because he was inspired by Westerns. He looked up to the cowboys on the screen as men of self-reliance. In his life, he subconciously sculpts himself into a cowboy: in everything from his facial hair and wardrobe, to his prowess with combat and cards.

Turner trains in card sleight of hand for 18 hours a day. He falls asleep with a deck of cards and wakes up with a deck. When awake, he’s basically never not practicing.

Turner also has a black belt in Karate. Earning this involved fighting ten other black belts in a row. These guys weren’t holding back just because he was blind. In the middle of the fight, he broke his arm. Still, he kept on fighting.

Growing up, Turner’s mom offered little support. Neither did the wider culture of toxic masculinity. It’s telling that Turner’s sister is also blind, and is able to “come out” with her disability earlier in her life than him. Gender probably played a role.

Turner’s deeper problem was that he never wanted to be seen as weak.

The pivotal scene in the movie comes when Turner meets Machaila, a girl who accepts her blindness.

“She doesn’t have any self-pity, which cost me a few years of my life,” says Turner.

Mikaila says, “I try not to let being blind get me down. But it’s hard sometimes.” Mikaila accepts the both-andness of being blind: that it’s good not be stuck in a victim identity AND it’s also good to accept when things are hard.

Turner tells her that he didn’t learn braille, in effect, because doing so would mean accepting he’s blind. Mikaila acknowledges that braille can be onerous, but she says it’s worth learning it in in the long run.

I teared up watching Turner and Mikaila talk. Though Turner is older in years, in many ways, Mikaila (who is probably around 10) is more mature. She models acceptance and vulnerability for Turner.

Acceptance = admitting your weaknesses to yourself.

Vulnerability = admitting them to others.

There is a scene when Turner moves his arm in front of his field of vision. His brain simulates the arm’s motion (a neurological condition called Charles Bonnet syndrome). For a while, Turner’s denial of his blindness was so strong that he didn’t realize that what he was seeing was not real, but a simulation.

Over time, Turner “gets over himself” and admits his blindness publicly. He does a one man show, “Winning with the hand you are dealt” in which, for the first time, he publicly owns his blindness.

Psychologist Carl Rogers said, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.”

How did Turner change?

He gets a seeing-eye dog. He softens up a bit. This doesn’t make him a worse magician. In fact, it made him more real and relateble. Less of a characature of a maverick cowboy, and more of a human.

I once met someone with a genetic disease that was causing weakness of the legs. She was living her best life: she had a romantic partner and a job and was in great spirits. She told me about her sister, who was older and, though less weak than she, was depressed becasue she was keeping the disease a secret.

Secrets are often sinister, it seems to me. In Meditations, Marcus Aurelius talks about one thing he admired in his step-father: “How few secrets he had.”

Dealt finds the universal in the specific. On its face it’s about a blind magician, but it’s really about our relationship to our weaknesses. Do we keep them a secret and live as if they did not exist? Or do we admit them to ourselves and to those around us?

Minimization of secrets is a good ideal to strive for.

3. Discipline begets discipline.

Listening to the Tim Ferriss podcast with Turner taught me that discipline has the ability to create an upward spiral in our lives. Let’s say I start flossing. The flossing itself may not make my life that much better. But by showing up for myself, I am teaching myself that I can improve my life. That I can change. That I can be relied upon. Discipline begets discipline.

And so, “cheating” negates the benefits of discipline. Let’s say I take a week off from flossing. This gives me the impression that I am not reliable, not to be trusted.

Discipline, it seems to me, is a very helpful virtue to cultivate, for it can really be the thing that gets us on the right path in life.

4. Progressive desensitization is the way through fear.

Turner talks about how he deliberately pursues what scares him: he eats live cockroaches and fish eyeballs, does karate against sighted opponenents. This daily habit of going through fear is called progressive desensitization, and Turner is an embodied example of how this can work in real life.

Turner still feels fear. But he uses discipline to keep pushing himself into what scares him, instead of avoiding it. If we push ourselves into the wall of fear, we get better at going through it.

Progressive desensitization has worked for Richard. Instead of ending up a drug addict, afraid of life and stuck in a victim mindset about being blind, he has become a total badass.

5. We can create our lives.

Turner is creative. He creates novel card moves, he built a 3-story deck for his house, he named his son Asa Spades, to name just a few of his creative acts. In the podcast, he talks about a turning point when he was abusing drugs and went to a park to buy some PCP. There, he met some evangelical christians.

He had this epiphany: if humans were created in God’s image, then humans are creative. Humans can turn earth into microchips. So, he resolved to start living creatively.

Turner has taken his gifts (such as Charles Bonnet Syndrome and a photographic memory) and has applied the heck out of them. He has taken the challeng of his blindness and excelled in spite of this.

We all have limitations: limited abilities, a limited lifespan. Turner is inspiring because he had more limitations than most, and was able to make something extraordinary of his life.

This brings me back to Lesson #1: being extraordinary is not necessary or sufficient for a good life. But being creative, I think, is. Every human, whether or not they think of themselves as an artist, needs to own their creativity.

One way to think of a human life as as a blank canvas. We all have a limited amount of space on which to paint. It takes creativity to paint the painting that most aligns with our deepest values.

For me, it has taken some creativity to let go of potential careers in magic and filmmaking and science, and embrace the many ways I can find meaning in neurology, and in writing as a hobby.

I intend to keep creating my life, with discipline, with acceptance of my flaws, and by continuously pushing my way through fear.

I have Richard Turner to thank for this inspiration.